#11: Thoughts on Varsha Rutu - The monsoon season in the Indian calendar

As we enter the last week of Varsha Rutu, the season of rains here in India, here are a few thoughts on the timing of the season in the Indian calendar system, how our experience of the rains fits into the scheme and about a few traditional practices followed in this period.

In the Bhāratiya tradition of calculating time, a year is called a Samvatsara. In every Samvatsara, there are two Āyanas - based on the movements of the Sun, the Uttarāyana and Dakshināyana, the northern movement of the Sun starting from winter solstice and southern movement of the Sun starting from summer solstice. The Samvatsara is also divided into six Rutu-s or seasons. Each season is further divided into two Māsa-s or months. So for every year, we get 6 seasons and 12 months.

Varsha Rutu is one of the six seasons of the year, consisting of Shrāvana and Bhādrapada Māsa. Two months of the year when there is Varsha - rains. But, when I think of it, rains last way more than 2 months in much of India. Especially in my home state of Karnataka, our rains start from early June and last till mid/late September - a good four months of the year. Areas like Bangalore even get rains much later during the year as well. So why is there only 1 Varsha Rutu spanning two months, why not 2 Rutu-s and 4 māsa-s, which is what we actually experience?

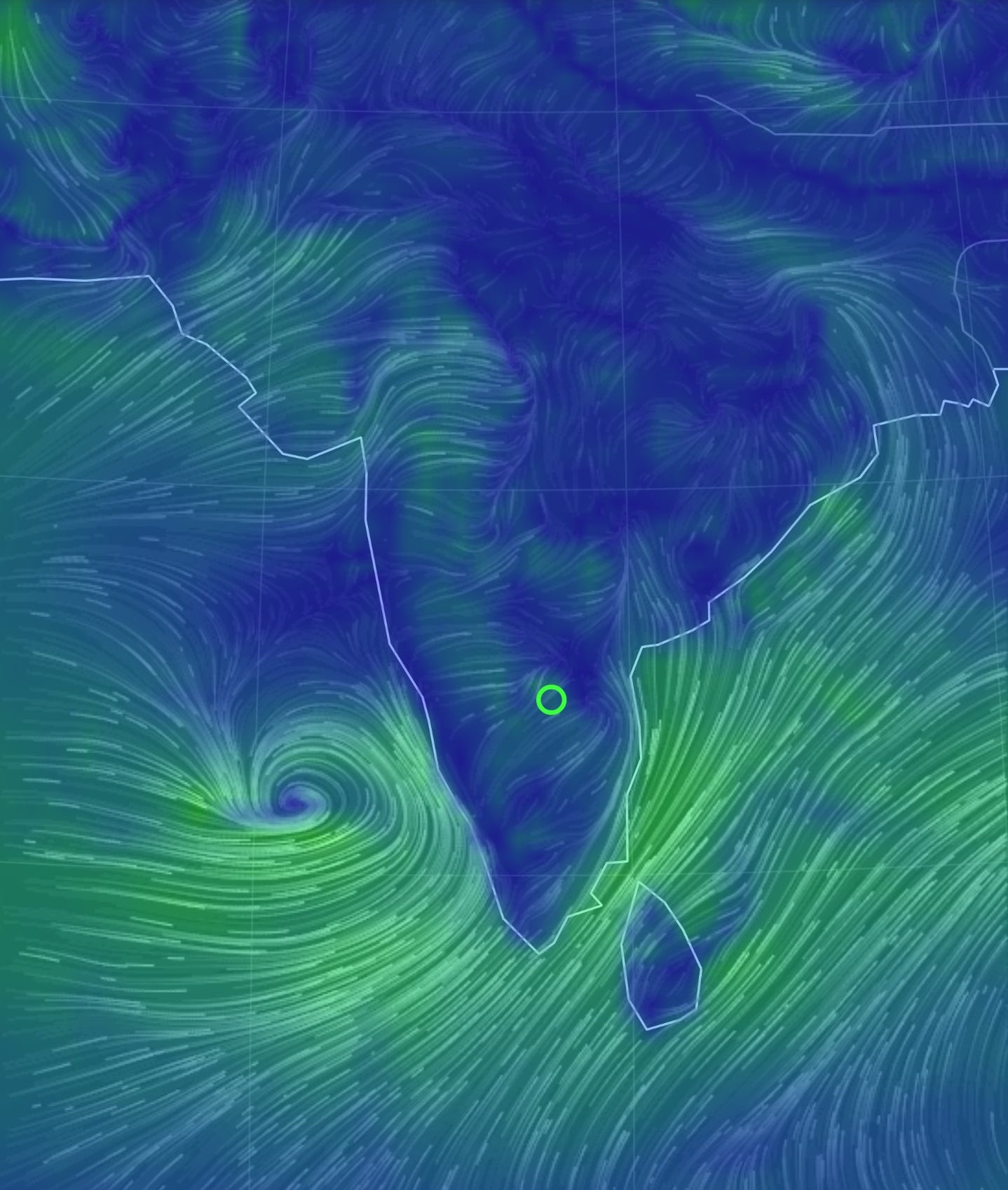

The Life cycle of the Indian Monsoon

To answer that question is not easy, well there is no clear answer either. When I was living in the northern Indian town of Rishikesh, it seemed like the rainy season was much shorter. While there were heavy spells of pre-monsoon showers, the real ‘monsoon’ rains started only in end of June and they would generally last till mid September. So, that was 2 and half months of peak monsoon experience. Does this make the conception of Varsha Rutu more sensible for North India than for southern regions? But why do people across the country follow the calendar?

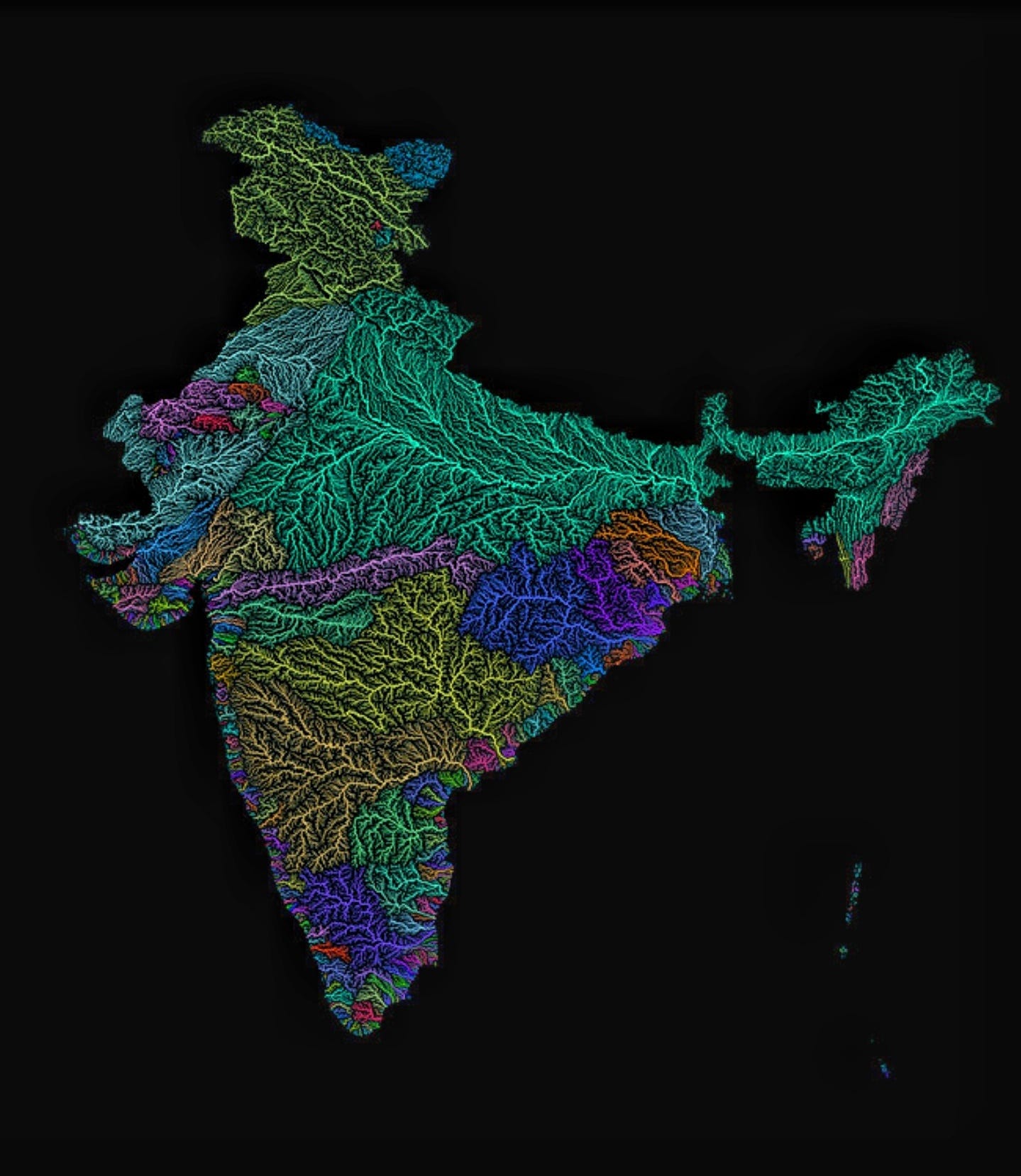

The way towards a solution to this predicament was to look at the entire geography of the Indian sub-continent, the Bharata Varsha, and observe the movement of the monsoon throughout the year more closely.

The life-cycle of the monsoon rains in India is such that the rain-bearing clouds enter from the south-west, collide with the Himālaya in the north, and return back through the south east. That is, the south-west monsoon rains enter India near the Sahyādris in June, which is the end of Grishma Rutu in the Indian calendar. And by the time Varsha Rutu - the season of peak monsoon rain - comes about in July, the monsoon is spread over all across the Indian sub-continent. The Varsha Rutu generally ends in the middle of September, giving way to Sharad Rutu, or the autumn season, which is when the rains travel back through the south-east regions of India, which is why parts of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh get most of their rains in Sharad Rutu.

This amounts to a circular movement, a form of pradakshina of Bharata Khanda by the monsoon, which lasts a full 6 months, with the north east monsoons lasting as long as December in parts of Tamil Nadu.

What then is the Varsha Rutu?

The rationale of having only one Rutu and two Māsa-s dedicated to the monsoon rains, seems to be that during the two months preceding and the two months post the Varsha Rutu, the monsoon clouds are travelling, i.e., the rain-bearing clouds are in the process of moving up north in Grishma Rutu (Summer season) and are moving back down towards the south in the Sharad Rutu (Autumn season). So the two months when every corner of Indian sub-continent is encompassed by rain-bearing monsoon clouds, the period when every inch of India gets rainfall, is considered the Varsha Rutu.

The latter half of Grishma Rutu is called the Āshada Māsa, and is typically associated with heavy winds, as much as they are with heavy rains. It is the time when the winds carry the rain bearing clouds all the way up north till the Himalaya. Anyone who has lived in the northern Indian plains for long enough would have experienced heavy dust and wind storms during the late summer months. This northern travel of the monsoon is beautifully narrated in the legendary poet Kalidasa’s famous poem Meghaūta, where Megha (clouds) become his Dūtas (messengers), conveying a message from central India where he lived, to the Himalayan mountains, where his wife awaited him.

Thus, while Āshada MĀsa does receive rainfall, since the monsoons are still moving through the Indian land-mass, it is not yet time to bring in the Varsha Rutu! The same can be said about the rains post the Varsha month, while it is still raining in parts of the country, the monsoons have already left for good in some other parts, hence, the calendar moves on to autumn :)

The conception of Chātur-Māsa

If the above explanation about Varsha Rutu is not sufficient, there is another traditional conception that recognises the monsoons rains of India. It is called the Cātur-māsa (literally 4 months). This spans from Āshada Ekadashi to Karthika Ekādashi (generally late June to late Oct), which is absolutely in sync with the monsoons that most of us experience, at-least for those of us in southern India.

These four months are considered sacred and some of the most important Indian festivals fall within the period, where one spends a lot of time with their family and the community around them. During the Chāturmāsa, people are discouraged to travel and are supposed to stay in their own villages/towns/cities. There is vrata (observance of a vow) which needs to be undertaken where only the locally and seasonally available food is consumed. So, in a sense, travelling far even for supplies is discouraged.

The Chāturmāsa conception is especially followed by Sansyasi-s (ascetics who have renounced worldly life), which we can see across the many Matha-s (monasteries) of southern India. One of the Dharma-s or duties of a Sanyasi is nitya sanchāra (everyday travel), they are not supposed to stay in one place for more than a day. But in these four months, they are advised to cease all their travels to stay put at one place. Monsoons are a difficult time to travel, especially on foot. It is the time when insects and reptiles breed, when navigating rivers is dangerous, hence, it is natural that travelling is abandoned. The focus instead is on intense study and reflection.

The above discussion tries to illustrate that while Varsha Rutu is the period of intense rains throughout the country, the Chāturmāsa represents the larger period of monsoons which we all experience, and our customs, traditions and calendar, all reflect the same.

This was but a rudimentary reflection of how the Bharatiya conception of time, dates, seasons and traditions are all beautifully in line with our experience of the world around us. Unfortunately, we have abandoned a system of calculating time based on movement of natural phenomena like the Sun and the Moon, which is reflected in the names that our dates, months and seasons carry, with a system which is not at all suited for our geography. The people of Nepal are the only ones in the Indian sub-continent that continue to officially recognise and follow the traditional calendar. I hope this post plants a seed in your mind to reflect on this as well!

Watch this video in 2x speed on youtube starting from the 3rd minute, a timelapse of how the monsoons behave in Varsha Rutu, two months between mid-July to mid-September, which would help you understand what I have tried to convey through this post -