#10: Changing pattern of Indian monsoon and the role of Sahyādris

It is that time of the year in India, when there is a sense of joy. The dry meadows of the mountains have made way for lush greenery, the flowers of the shola forest have bloomed, the amphibians and reptiles are out and about; for it is their mating season, the farmers have finished sowing for their Kharif crop and are waiting for the rains. It is that time of the year when the entire landscape changes, when seeds sprout, rivers rejoice and the mountains mesmerise. It is time for the arrival of the great Indian monsoon for much of the sub-continent.

When the monsoon clouds meet the Indian landmass, it arrives with full pomp and glory i.e., with ferocious thunder and lighting. The first spell of rain that the monsoon brings is usually the fiercest - it rains as much in a fortnight in places like Agumbe as much as it rains in a year in the United Kingdom. How can any region withstand such enormous rains? The intensity of which is unmatched anywhere else on the planet? It is possible because on the southwest coast of India - where the monsoon strikes with all its might - there exists an incredible geographical phenomenon called the western ghats, which is aptly called the ‘Sahya’ parvata or Sahyādri.

Why do I call it apt? Because the word ‘Sahya’, like most words of Sanskrit, has multiple meanings, all of which apply to this mountain range. The word ‘Sahya’ means one that withstands, tolerates, that which is able to bear and endure. And true to its name, the Sahyādris not just soak in some of the highest rainfall in the world, but also nurture over 20,000 different species of plant and animal life. ‘Sahya’ indeed, no? Could there have been a more meaningful name?

The usage of the name ‘Sahya’ to refer to this mountain range isn’t a new phenomenon, we find it in texts like the Mahabharata and the Vishnu Purana, where it is listed among the seven revered mountain ranges of the Indian sub-continent - the seven kula parvatas of Bharatavarsha. But it was when I was reading Vādiraja Thīrtha’s epic travelogue ‘Thīrtha Prabandha’ where he uses the word ‘Sahya’ to put his point across humorously did I realise the profoundness of the meaning. Vādiraja Thīrtha, a 15th-century Vedānta philosopher, while crossing the Sahyādri range while on his pan-India pilgrimage composed a beautiful shloka in its praise -

सह्योsप्यसह्योsसि गिरे पापानामस्तु तत्तथा |

अचलस्त्वं चलसि मन्मसस्तन्न रोचते || ५८ ||O mountain! Although you are called sahya (tolerant), you are very asahya (intolerant) for those who are sinners. May it remain so! But then, though you are achala (immoveable), I do not like the fact that you are chala (unsteady) in my mind. (translated by Hariprasad Nelliteertha)

So, based on the semantics of the term Sahyadri which Vādiraja Thīrtha highlights, I think it is safe to deduce that they are named so because they are considered ‘Sahya’ because they perform two important functions - one, to withstand the fury of the monsoon when it strikes the subcontinent, soak all the rain and then drain it down through its rivers; and two, they nurture and bear innumerable lives which thrive in its dense forests.

The semantics is beautiful, yes but one may ask why is all of this relevant? Because in the last few years, we are getting to see what happens when the dynamic between the monsoons and the Sahyādris gets disrupted.

When monsoon no longer hits the Sahyādris - Observing a trend

Sahyadris are the crucial first point of contact on the Indian landmass that withstands the fury of the monsoon. But what happens when the monsoon clouds no longer meet the subcontinent where it generally does - into the mountains of Kerala/Karnataka - and change their course? What if the Sahyādris no longer get to perform their function? Here are a few observations.

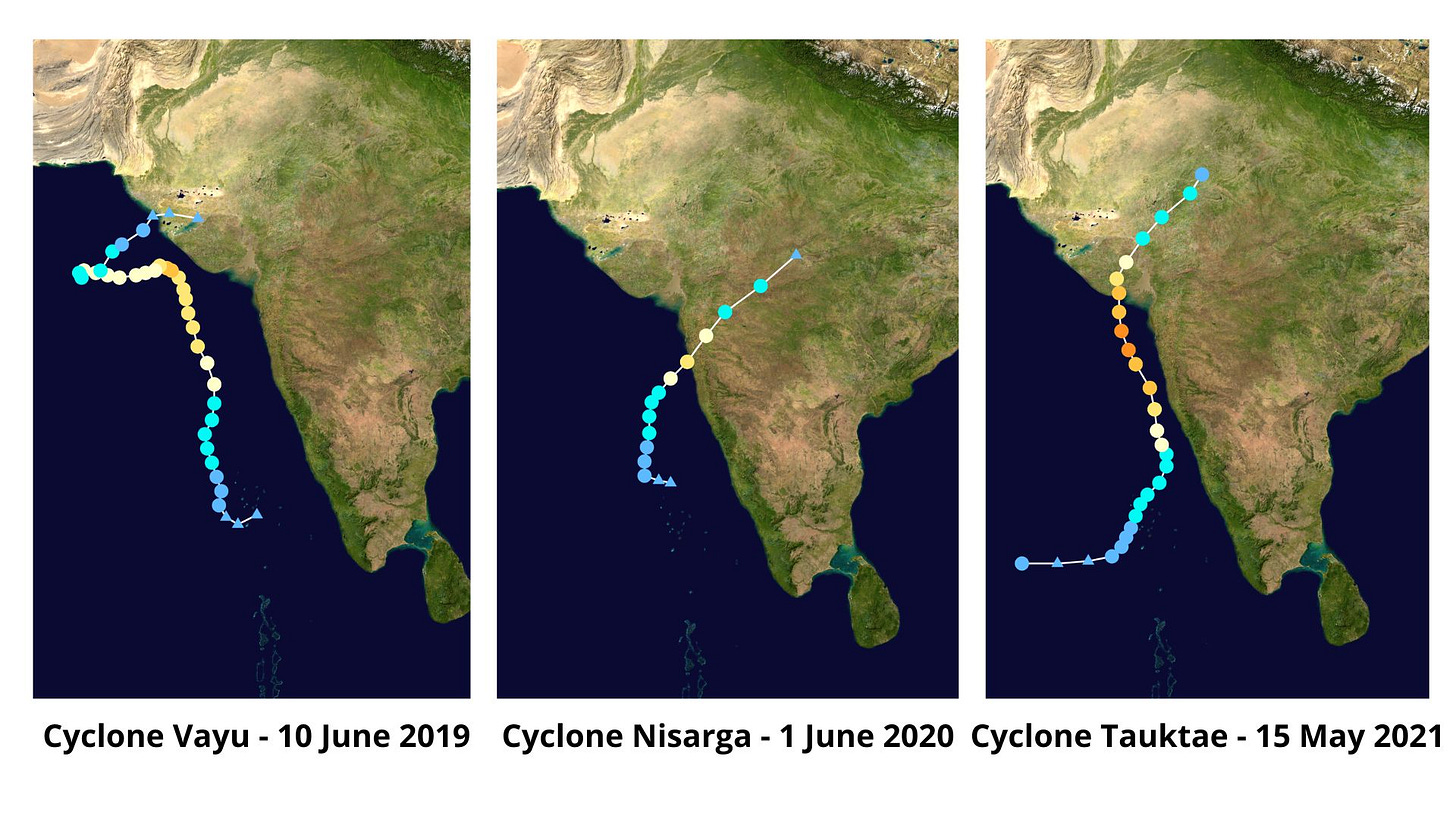

In each of the last three years - in 2019, 2020 and 2021 - just at the end of the summer season, right at the onset of monsoon, there has been a cyclone of varying intensities in the Arabian sea, just off India’s west coast, where the moisture-laden monsoon clouds are formed. And the landfall of all of these cyclones have been in Gujarat or Northern Maharashtra. Carefully observe the image below of illustrations of the three cyclones and their directions.

These cyclones are categorised as ‘Very severe’, ‘Severe’ and ‘Extremely severe’ cyclonic storms respectively, hence their intensity is directly comparable to the monsoons, if not more. Also, observe the dates closely, all these cyclones occur at the end of the summer season in southern India, just when the monsoon is about to arrive, which is disrupting the weather pattern as well as the ecological system of the western ghats. It is important to note here that these cyclones start forming at least a couple of weeks before they actually make landfall.

Why is this problematic? These cyclones are pulling all the rain-bearing monsoon clouds built up in the south-western Indian Ocean and depositing them beyond the Sahyadris, in parts of Maharashtra and Gujarat, which are not at all capable of withstanding the initial burst of the monsoons. And this in turn is leading to floods in Gujarat, Maharashtra and even northern Karnataka, disrupting not just the lives of people, but innumerable species of plants, insects and animals. Over these three cyclones, over 200 people have lost their lives, and over 55,000 homes were damaged, not to forget the damage to crops and other physical infrastructure, all of this because the Sahyādri mountains that soak in the impact of the initial burst of the monsoons are not able to do that. In a sense, when the ‘Sahya’ is not there, then we are all in a state of ‘Asahya’ - unbearable.

Second-order effects on people, animals and forests

Having lived on the Indian Coast in Udupi, a district which receives probably the highest rainfall in the entire sub-continent, I had an opportunity to interact with people about how this recent trend has changed their lives. Beyond the immediate destructions that these cyclones bring about in regions where they make landfall, the moisture-laden clouds that they swallow from the Indian Ocean mean that the first impact of the monsoon in Karnataka is weak, with reduced rainfall in June. This is usually the time when everyone from farmers to fishermen plan their activities expecting a high volume of rain. But more than people, it is the animals and birds that are affected by these changes. The first major rains of the monsoons signify a time for heightened activity as well as the time of breeding for a lot of amphibians and reptiles in the coastal Karnataka and Sahyadri region. The disruption in the monsoon pattern means that their cycle is disrupted. Unheard of heavy rains before the onset of monsoon also affects birds as a lot of plants and trees that flower in spring tend to give fruits during the summer, which get destroyed or spoilt with heavy rains. While we artificially manage such issues for summer fruits like Mango through chemicals, birds, squirrels and monkeys dependent on berries/fruits have nowhere to go.

I wish I had information from Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) to justify all these points with hard data but I don’t seem to find any open source data on monthly rainfall patterns and can only rely on my observation staying on the western coast and interactions with people who live in the Sahyadris.

Story of 2022 - Same but different

What about the current year? There was no cyclone on the west coast in summer this year but there was a low-pressure weather pattern on the eastern coast which affected the western coast and the Sahyādris. While it was just a low-pressure system, the effect it had was similar to a cyclonic storm. In 2022 summer - in May especially - it rained heavily across the Sahyādirs. Living in Udupi, where summers are extremely hot and dry, I do not recall having a dry spell for three continuous days, it was extremely wet and nobody had any idea what was happening, the locals were flabbergasted. For this year, I have data though. In the summer months, we had more than double the average rainfall of the period. Yes, more than double. This report based on IMD data says, “South Interior Karnataka recorded the highest surplus % rainfall at 131% with rainfall of 324.5 mm compared to normal rainfall of 140.4 mm”. Check the map below, the southwestern coast is marked as ‘large excess’ for the period between March and May 2022.

While I did not get data for previous years to prove my hypothesis that heavy rainfall in May reduces rainfall in June, a pattern very apparent for anyone living in the region, 2022 June data makes it very clear what is happening. India’s south-west coast, home to the Sahyādris, where monsoons strike with all its fury in the month of June, had up to 50% deficit rainfall for the month, from Kerala to Karnataka to Maharashtra, there is a huge deficit! Check the map from IMD below -

There is no easy way to conclude such a post. As someone who grew up hiking in the Sahyādris and having worked in the mountains for a decade now, these patterns are alarming and unsettling. These are not just passing spells of unseasonal rains or heat wave patterns which last for a week, what we see is an inversion of everything we have considered normal till now - sustained heavy rain in summer and month-long dry weather in the rainy season - such patterns change the very meaning of the words like summer! While such events are disrupting the landscape and the people which I so dearly care about, I am not sure as an individual I am in a position to do anything beyond putting these observations out. I had never believed I would see the Sahyadris devoid of rain in June, but here we are! All I can do though, like Vādiraja Thīrtha, is to pray to the mountains and the rain gods to restore the balance.

PS: I know I have not posted here for 3 months now. I was tied up with working on a paper for my Master’s degree. I have paused the billing for all paid subscribers so that you get an automatic extension of your subscription duration. That said, hope to make up for lost time from now onwards. Thank you!